At its heart, 'Ammonite' is about the human ability to change and adapt to our surroundings versus the drive towards stagnation and death. Marghe undergoes a physical transformation when she is infected by the virus, gaining augmented senses and abilities, but she also changes as a person as the experiences she undergoes on Jeep force her to confront her issues. Marghe starts the book as an angry young woman. She has no love of Company, having worked for them on the mining planet Beaver and suffered at their hands, and has only signed up for the job on Jeep for the unique opportunity to study its population, and she's very bitter about her mother's death and her relationship with her father. Following being captured by a violent tribe and a grueling escape across winter wastelands, she is taken in by a family of indigenous people. One of them, a woman called Thenike, is a viajera, a sort of travelling story-teller/healer. She nurses Marghe back to health, and asks Marghe the quote at the top of the page. I have to say, as someone who in their youth moved from place to place a lot, and who has difficulties making connections with people at times, I found it a deeply resonant scene. This is the catalyst for Marghe's transformation; she makes a conscious decision to stop taking the vaccine, to become a part of Jeep and its people, and to become a part of Thenike's family. It's really moving stuff, and the tone is expertly handled by Griffith.

As Marghe enters into a relationship with Thenike and starts to become a viejera herself, Company intercepts a garbled message from Marghe to Commander Danner at the Company base, and mistakenly believes that the vaccine has stopped working. Danner and the other on-planet Company personnel have to escape the base before the Company warship destroys their base, and figure out how to cooperate with the other tribes in the face of the oncoming winter and Uaithne's swathe of destruction. Marghe and Thenike return to meet the Mirrors, to help the negotiations, and Marghe winds up confronting Uaithne. The Echraidhe live by their strict traditions to help them survive the harsh winters of the north, but their numbers are dwindling. Like the stranded Mirrors and Marghe herself, they are faced with the choice of change or death. Uaithne sees herself as the Spirit of Death, and has whipped up the Echraidhe and other tribes in the north to go out in a blaze of violence. She represents the forces of stagnation and death. Marghe defeats her by using her new skills as viajera to adopt the mantle of the spirit of change, and is able to talk the tribes out of war. This provides a nice little meta-narrative, about the power of symbols and the importance of story telling, as in The Book Of The New Sun by Gene Wolfe. However Griffith wisely doesn't let our characters off the hook by short-circuiting the conflict; while disaster is averted, some people on both sides still die, and while everyone agrees to sit down and talk, the solution necessarily involves compromise and so is not perfect for everyone.

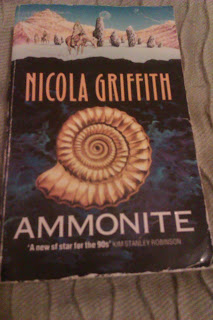

'Ammonite' is a pretty incredible book. Its concept of a world where women are the only gender is reminiscent of Whileaway from Joanna Russ' classic 'The Female Man', and in its story of a representative of another planet undergoing a journey of discovery both about themselves and the people they find themselves interacting with echoes Ursula Le Guin's 'The Left Hand Of Darkness'. However, 'Ammonite' is very much its own beast, and Griffith brings her own talents to good use here. The relationship between Marghe and Thenike is done really well; I've read a lot of SF and Fantasy where relationships are either cursorily chucked in so that the protagonist could have a love interest, or characters are forced together simply because the author wants them to be together, but here the relationship develops organically and believably. Most of the characters, however minor, are well developed, and it's a nice touch how Danner's character arc parallels Marghe's. Jeep is also positively crawling with inventive alien fauna and flora, Griffith clearly has fun inventing all sorts of bizarre plants and animals while somehow managing to stay within the range of scientific plausibility. At the end of the book there are still unresolved tensions between many of the characters, which is a more realistic and adult approach than just tying everything up with a happy ending. After all, as Marghe herself notes:

"Marge thought about her mother, of the miners on Beaver, of Danner, of Aoife; of herself. People could not be made to change. It had taken her a long time to learn that. People had to want to change themselves."